This is the second in a five-part series about each of my five names. You can read the previous part here: “My name is Moshe.”

I am drawn to people who have the same name as me. Why? I can’t help but think that we share something more than just our name. A common identity, perhaps?

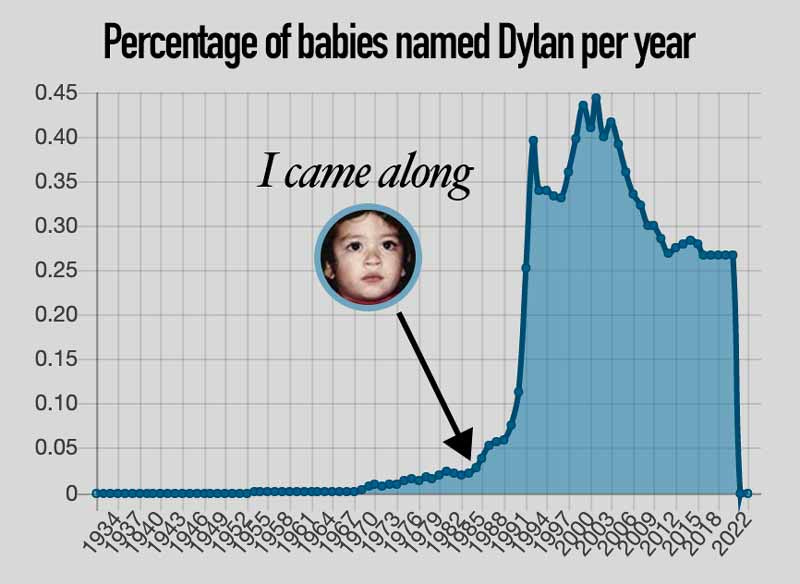

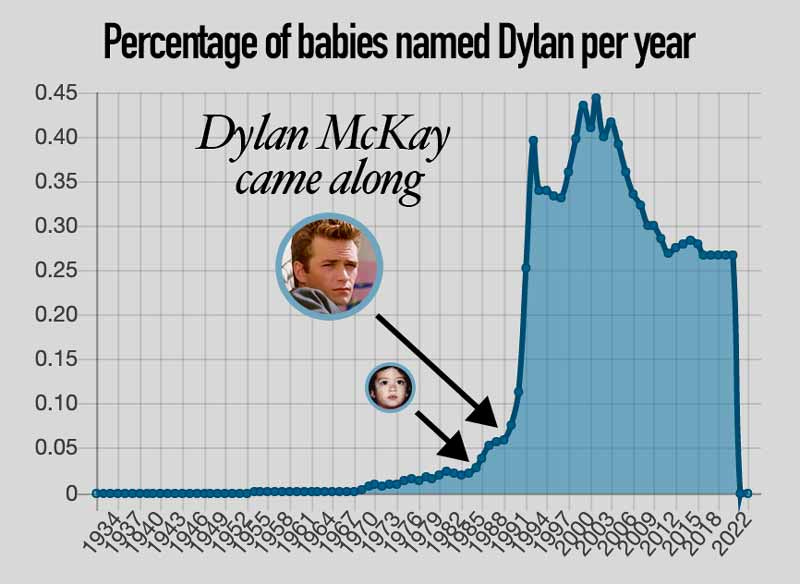

I get that a name is given to different people for different reasons. Still, I look for the connections. All the more so since my name, Dylan, is a little unusual, and was especially unusual when I was a kid. So when I did run into someone with my name, I figured there had to be a reason. Why are they named Dylan, like me? What do we have in common?

Growing up, when I told someone my name, there was a good chance they would reply by mentioning one of three famous Dylans. All three Dylans happened to be poets. To this day, I see myself connected to them. And it’s not just because we all have great hair.

“Hi, my name is Dylan,” I would say.

“Ah, like Dylan Thomas,” a school teacher might reply. As a kid, I didn’t know much about the early 20th century Welsh poet, but I had the sense of him being this traditional, well-respected literary icon who would forever be cemented in the early modern canon. I liked that.

“Like Bob Dylan,” a long-haired former hippy at my synagogue would beam. I noticed the way Bob Dylan made my parents’ friends feel young again, and made my own adolescent friends feel a part of something important. This man was magic.

“Just like Dylan McKay,” my older brother’s friends would say. Back then, it was hard for kids not to bring up McKay, “the 90s James Dean,” from the hit TV show Beverly Hills 90210. He was the poet of cool. In my first summer at sleep away camp, I bunked with a kid named Brandon, the name of the show’s other male heartthrob. Needless to say, Brandon and I were ecstatic to partner up. There was this feeling that camp that summer was going to be wild. I should mention we were 8-year-olds at the time, literally the two youngest boys, and this was a tennis training camp.

Admittedly, while I felt an aspirational link to these three Dylans, my knowledge of them when I was young was fairly superficial. I will say this, though: today, I know a few things more about them than I did before. Things that have actually led me to double-down on my belief that we Dylans are cosmically connected.

It all comes down to two things I now understand about Dylan Thomas, Bob Dylan, and Dylan McKay. The first is this: they, too, are middle children, each in their own way. The second is this: they had an aversion to bridges.

I found the second detail particularly surprising. You would think that a middle child would be all about the bridges. We live in the in-between, after all. We mediate, translate, and facilitate, and because of that, people look to us for help. Whether it is humdrum matters, like moderating a family discussion about which Netflix show to watch on a Friday night, or crafting poetic prose that help readers imagine new ways of perceiving the world. For a long time, I have seen my role in life as a bridge-builder. Even my career as a product designer has basically been helping colleagues better understand each others’ vision, in addition to their own.

And yet, the three Dylans I grew up with were middle children and bridge burners, one and the same. How could this be? Let’s go through it, one by one.

That’s what he said. Dylan Thomas is heralded by some as one of the greats. He was a lyrical wordsmith whose Romantic style harkened back to the 19th century. Sounds a lot like a dignified, well-mannered traditionalist. And yet, the writer has been criticized by the literary community as an overly effusive drunk who couldn’t write unless he was intoxicated.1 But also this: “There was a further characteristic which distinguished Thomas' work from that of other poets. It was unclassifiable,” writes Alan Simpson in The Poetry of Dylan Thomas. His unique style was acutely lyrical and emotional, with vivid imagery and an imaginative use of language. It was an island unto itself that could not be bridged. Nor did he have much interest in bridging it with the rest of the literary world. “In his life he avoided becoming involved with literary groups or movements” (Poetry Foundation). If this is what made him so great, it is also what made him so largely ignored rather than studied over the last several decades.

Bob Dylan is regarded as one of the greatest songwriters of all time. And yet, his signature song structure didn’t fit the popular mold. Here’s why: he was skeptical of bridges — that section of a song about three-quarters of the way in that introduces a musical change of pace in contrast to the verse and chorus. “Most songs have bridges in them to distract listeners from the main verses of a song so they don’t get bored.” To Bob Dylan, bridges are lipstick on a pig. Somehow, Bob Dylan’s definitive songs, composed of only a few chords and a sprawl of verses, managed to “contain multitudes: prophecy and hogwash, morality and absurdism, apocalypse and intimacy… he has lines like weapons and lines like benedictions.” (John Pareles, Rolling Stone). While on the one hand, Bob Dylan connected popular culture with counter culture, singing protest songs at Martin Luther King Jr.’s March on Washington and penning tunes like The Times They Are a-Changin', he famously cautioned his audience, “This here ain’t a protest song or anything like that, ‘cause I don’t write protest songs . . . I’m just writing it as something to be said, for somebody, by somebody.” It is puzzling. But that’s the point. He didn’t guide you. He staked his own ground, and left you on your own to find your own way.

Dylan McKay belonged to a broken family, leading him to struggle with anger, booze, and cocaine. A classic bad boy. At the same time, Dylan McKay was actually bookish. A fan of Virginia Woolf, we first meet him alone on the campus steps reading the book he keeps hidden in his black leather jacket. He tends to speak in adages, puzzles, haikus. In an alternate universe (or a 90210 reboot), Dylan Mckay could be a famous writer. This Dylan would have inspired the MTV generation back in the day to trade in their JNCO jeans and chain wallet for a fitted leather jacket with a pocket compendium of Woolf quotes. Instead, his unstable childhood threw him into an endless cycle of anger management woes, drug addictions, and volatile love/hate relationships with friends and lovers. His modus operandi was burning bridges. So much so, this fan created a video compilation of every bridge he ever burned throughout the seasons. He didn’t write poetry with his pen. He wrote it with his pain. He lived his truth. When the show ran, the bridges he burned lit up our TV screens. And we watched.2

What I admire about all three is that they weren’t trying to prove anything with their respective aversions to bridges. They were just sort of being who they were. This resonates with me. I mean, I just recently quit my design job in Manhattan (the island with 21 bridges and 15 tunnels to its name) so that I could live on the island of Oahu in Hawaii, far away in the middle of the Pacific. No bridges here. It’s not that I don’t see myself as a bridge-builder. I very much am and expect I always will be. It’s just that maybe, I haven’t given the bridge-burning side of me enough room to breathe. I mean, there are days where you just have to put your foot down. And not so that someone else could use it as a stepping stone. So that you can simply feel present where you are.

In fact, I was named Dylan after my great-grandmother. Her name was not Dylan. It was Helen. I’ll be sharing more about her in a post about my other Hebrew name, Hillel. I know. Kind of confusing. I’ll explain…

It is an Ashkenazi Jewish tradition to name a child after a relative who passed away.3 If the name isn’t going to be a one-for-one match, it is customary to pick a name with the same first letter, or with the same general sound, or with a similar meaning. If I was going to be a girl, my name would have been Ilana. As a boy, my parents were close to naming me Elon. But they just didn’t like Elon. “Dylan was cool,” dad told me over the phone the other day. “But we still weren’t sure about it, even after we named you. It’s an unusual name. Welsh. And it didn’t really sound like Helen.”

Mom went on to share that when they did name me Dylan, they fancied the idea that Dylan could be another way of spelling d’Hélène, French for “of Helen.” I like this story, but Dad was quick to cast it aside. “Yea, but it was a stretch,” he said. “That’s not really why we did it.”

Mom4 and dad got a little creative. To make up for Dylan feeling a little off the mark, they gave me an additional Hebrew name when I was born. Hillel. This way, somewhere between the sound of Dylan and the sound of Hillel, there would be a semblance of the sound of my great-grandmother’s name, Helen. I get the sense that my parents still feel a little unresolved about this decision. It is an imperfect one. And it strays a little much from standard Jewish naming convention. At the same time, I also sense they take a little pride in the creativity of it. I find it very poetic of them.

For now, I’ll just say this about Helen. She liked to cook, like I do now. And it’s nice knowing she’s there between my names. It doesn’t matter if it is a little unclear exactly where between the two names you find her. I don’t need it to be any clearer. She is there.

◆

FOOTNOTES

Novelist Sir Kingsley Amis went so far as to describe his lyricism as “frothing at the mouth with piss.”

Here is the synopsis for the quoted episode (Season 5, Episode 8, “Things That Go Bang in the Night”):

Val wants to move back to Buffalo, but her mother has checked into a mental facility. Brandon asks Steve and to give Val another chance. A pool hall acquaintance supplies Dylan with drugs. Brandon behaves coldly toward Valerie after she skips a party to go to Dylan's house. She reveals the gravity of Dylan's situation and pleads with Brandon for help. Dylan finds his gun and points it at brats who vandalize his house on Halloween. He shoots up his living room. Brandon confiscates Dylan's gun, ignoring his threats of legal action. After Dylan passes out, he stays to watch over him.

According to the Jewish online magazine Aish, the tradition of naming a baby after a relative who passed “in a metaphysical way forms a bond between the soul of the baby and the deceased relative. This is a great honor to the deceased, because its soul can achieve an elevation based on the good deeds of the namesake. The child, meanwhile, can be inspired by the good qualities of the deceased – and make a deep connection to the past.”

Here, mom flaunts pearls in a funky “California girl” shirt as she sips her morning coffee from a mug that reads, “My Mug.” #queen