My name is Rosal

Between — first & last names, Filipino food, werewolf Bar-Mitzvahs, colonization, girls & gardens, tattoos, Spock, family parties

This is the third in a five-part series about each of my five names. You can read the previous part here: “My name is Dylan.”

Growing up, I was under the impression that my middle name was a critical part of my being. So critical, I was insecure about it. My grade-school friends all had middle names that sounded like first names. Mine, which is Rosal, is a common Filipino last name. When I told a friend my middle name, I suspected it sounded off. That it wasn’t the sort of middle name that they were looking for.

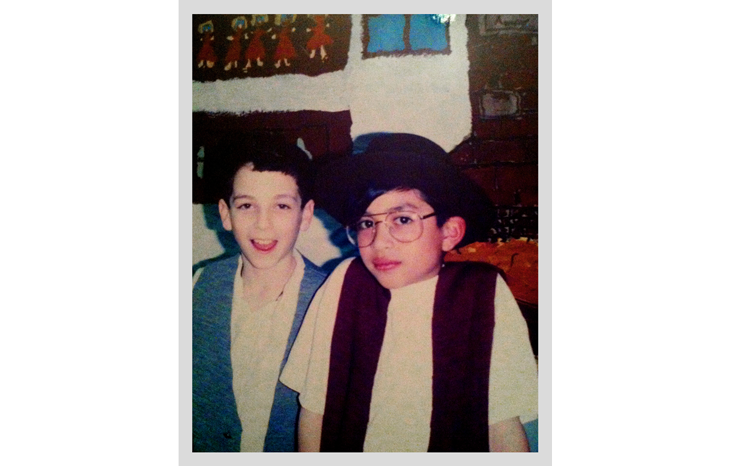

My older brother Arel has two middle names. His full name is Arel Jacob Rosal Greif. As a child, I was jealous. It wasn’t so much that he had the two middle names. It was that one of them, Jacob, sounded like a first name. Jacob also happens to be the first name of one of our cousins.1 Given everything I could deduce about middle names at the time, it seemed glaringly obvious to me not only that I was deprived of a middle name that sounded like a first name, but also, that my middle name should have been Jesse2, the first name of another one of our cousins.

I told my family that henceforth, I would be known as Dylan Jesse Rosal Greif. Needless to say, it didn’t stick.

And so I ask: what are you to me, middle name o’ mine? Do you complete me, or are you but another emblem of my all-around incompleteness?

Tradition

Perhaps I over-indexed on the significance of my middle name. I am fairly certain that skipping the middle initial field on tax forms and travel documents makes no difference whatsoever.

Or maybe I indexed it the right amount, but in the wrong place. Maybe I was making it too personal, when I should have taken a historical lens. Let’s go back in time, shall we?

According to this Time article, the modern western use of the middle name dates back to 13th century Italy, when upper class newborns were given a middle name after a saint, in order for that saint to protect them.3 Over the centuries, the practice spread across Europe and the U.S. as a way of signaling upper-class status. By the 19th century, middle names were prevalent across all classes, and instead of a saint, newborns were named after family or community figures, or for no reason other than the aspirational sound of it.

A much less common tradition in the U.S., but the dominant one in the Philippines, is to make the newborn’s middle name the mother’s maiden name.4 My middle name Rosal was my mom’s last name before she married my dad.5

I recently asked my mom about it.

I wanted your middle name to be Rosal because of the Filipino tradition. I wanted the ancestral name to show up. Because I want the history. Especially because I’m in America now, and I didn’t want to turn my back on the heritage. I wanted to make sure you all had the Rosal name.

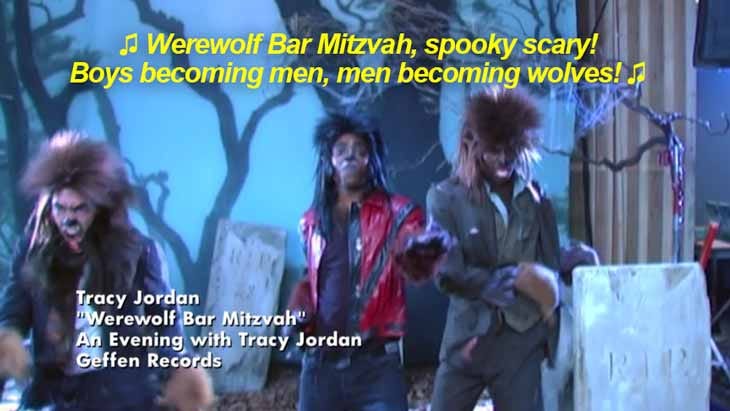

So. It’s a matter of tradition. Then again, I didn’t grow up in a traditional Filipino household. It leaned more Jewish than Filipino. I spoke more Hebrew than Tagalog. I ate more kosher than lechon6.

Let’s just say, I was getting a lot of mixed-rituals.

Furthermore, Filipino tradition is itself hard to define. Lechón is also enjoyed in Spain and Portugal. One of the Filipino treats I loved growing up, ensaymada, is found in Mallorca and Puerto Rico. Batok, the indigenous Filipino tattoo tradition, shares common tools, practices, and patterns with many other Austronesian groups, from Malaysia to Samoa to Hawai’i.

Heck, my middle name, Rosal, is a Spanish word. It means “rose bush” or “rose garden.” If you are wondering why my Asian mother has a Spanish last name, maybe it helps to know that the Philippines was named after King Philip II of Spain in the 16th century. Originally in the hands of the Portuguese (remember Magellan?), the islands were then colonized by the Spanish for over 300 years, before they were then occupied by the U.S. and Japan. At the same time, there are upwards of 130 indigenous ethnic groups each with their own language scattered throughout the islands, which adds even more to the diversity of the Filipino people.

None of this imbues me with a sense that my middle name “completes me” in any way. On the contrary, it shows me what a puzzling and incomplete specimen I really am. A mix. A mutt. A muddled melody. A montage of a man with a muddy, middle-name. #mood

Roots

What does one do at the face of this? I did what anyone would do. Knowing that Rosal means “rose garden,” I combed the internet for an audio lecture on the etymology of roses and gardens, and I found one.

This excerpt is from The History of English Podcast, Ep 137: “A Rose by Any Other Name”:

The earliest reports of rose cultivation can be traced all the way back to the ancient Persians…. Paradise is an ancient Persian word for garden…. The para part of paradise referred to the border or edge that extends around a particular area. It comes from the same Indo-European found in Latin words like perimeter and periphery. The dise part of paradise comes from the root word meaning to form or to build.

So a paradise was literally an area with a wall or barrier that had been built around the perimeter… Those barriers separated the garden from surrounding fields or forests, and they represent one of the most fundamental aspects of a traditional garden: it was a small controlled natural area within a larger, uncontrolled natural area.

My mom was not aware of these particular details about her name. But that notion of a rosal as “a small controlled natural area within a larger, uncontrolled natural area” — it captures some of the stories she tells me about her upbringing. My mom’s Rosal family lived in a house with a fenced-in perimeter, and roses actually grew on that fence. Not red ones, white ones. Pure ones.

I visited this house twice on my trips to the Philippines. Walking along that fence, I imagined my mother as a little girl running in and out of that house — the rosal flowers along the outside of the fence protecting the Rosal children living inside of it.

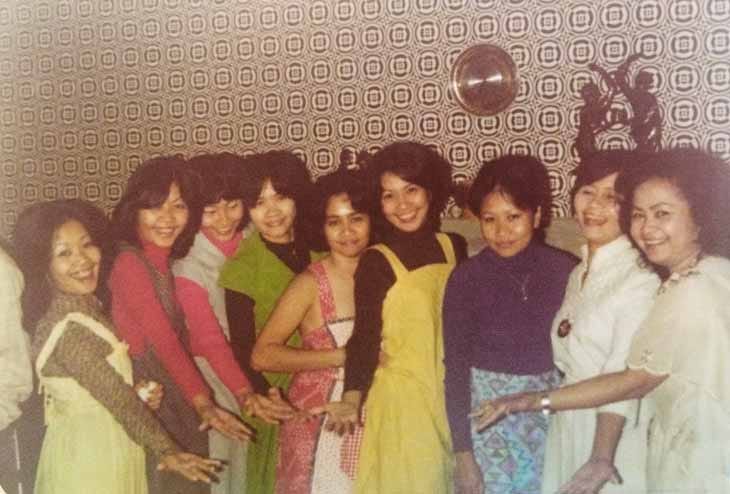

And that little paradise could afford some protection. My mom was one of nine sisters, and the house was across the street from a basketball court, where all of the neighborhood boys would play.7

They had a brother, Aurelio, but he was literally the youngest of the ten – hardly in the position to look out for everyone. Pang, my grandfather, knew he couldn’t protect all of the girls alone. “So he raised us like men,” my mom said. Tough. Independent. Hardly delicate. Rather thorny. Rose-like.

Mang, my grandmother, meanwhile, afraid her daughters would be tougher than a girl ought to be, invoked a phrase she would say whenever they ran out the door. “Be kind, be nice, be polite!” Somewhere between grit and kindness, the Rosal girls found their way. In truth, it may not have been the physical garden fence that protected the Rosal clan. Maybe it was the garden fence that the children carried within. The Rosal family name.

Far from fending off boys, the sisters had a way of absorbing them into their world. My mom remembers how now and then, a boy would enter the fenced-in parameter. He would wait in the courtyard between the fence and the front door, sitting on a swing. His date would still be upstairs, taking her time, doing her hair. I imagine girls, younger and older, skittering this way and that, making apparent to the boy that he was dramatically outnumbered.

My mom was one of the youngest. She remembers running up to those boys to ask them a flurry of questions. “They’d shoo me away,” mom said. “Get your sister, they told me. And I hated them for this.” My mom ended up building her own kind of fence. She vowed never to marry a Filipino man. Instead, she committed to marrying a Japanese man, a controversial move, considering that following Japan’s occupation of the Philippines in WWII, Japanese men had become the mortal enemies of Filipino men. “I guess, I figured not all those bad stories about them could be true,” she told me. She saved up money to buy a Japanese language book and she started studying. She never did marry a Japanese man. She went even more rogue. She abandoned the Catholic church, and married a Jewish guy from New Jersey, instead.

None of the boys who visited the house managed to take a Rosal for a wife. But many of the Rosal girls managed to take jobs that belonged to men. Virtudes, the first daughter, became a dentist. Bernabella, the second, became a lawyer. Paraluman, the third, studied architecture. Sonia, the fourth, became a nutritionist.8

A Rosal by any other name

I love this family story. About the boys across the street and the rosal fence that enclosed the Rosal family home. And then, a year ago, I learned that a critical detail of the story wasn’t true…

Rosal may mean “roses” in Spanish. But in Tagalog, the main language of the Philippines, Rosal doesn’t mean “roses” at all. It means something else.

I should mention that I learned this just a week before my appointment to get a rose tattooed on my arm. Back in the height of the pandemic, quarantining and mixing cocktails on the 37th floor of my sister Shana’s Honolulu high-rise apartment, we decided on a whim to get tattoos.9 It was an “if you do it, I’ll do it” kind of deal. Both you’s said yes, so neither I could say no.10 We would both incorporate roses in our tattoos. And we would keep this plan a secret from our parents until it was too late.

Then on Mother’s Day, which was a week before my tattoo appointment, Shana and I called mom. I couldn’t help but ask her to tell us more about the roses that grew outside her childhood home. “But it wasn’t roses,” mom said. “It was gardenias.”

“But I thought rosals grew on the fence outside your home.”

“They did. But rosal doesn’t mean ‘rose’ in Tagalog. It means ‘gardenia.’”

It was a good thing I called my mom on Mother’s Day. So the gardenia, not the rose, is my family flower. And it was gardenias that grew on the fence outside her home. Most likely the Gardenia Jasminoides, which is white, and double-blooms like a rose, but isn’t a rose, really.

It is pure coincidence that “gardenia” also happens to be associated with the word “garden” and is a synonym for paradise. This would leave intact that notion of my mom’s childhood home being “a small controlled natural area within a larger, uncontrolled natural area.”

Still, I felt a little silly. For 37 years, after living with the middle name Rosal, after resolving to get a freaking tattoo of a rosal on my arm, I never knew what my middle name actually meant. I spent the week before my tattoo appointment researching gardenias, starting with the most obvious question. Why would this flower, of all flowers, be named after gardens in general? The reason was underwhelming. Gardenias were named gardenias after the 18th century Scottish naturalist who first classified the flower. His name was Dr. Alexander Garden.

I discovered more interesting information in a 2011 paper called “A Revision of Philippine Gardenia” by K.M. Wong of the Singapore Botanic Gardens, published in the Edinburgh Journal of Botany. It reveals five varieties of gardenia that are endemic to the Philippines: Gardenia Barnesii, Gardenia Elata, Gardenia Mutabilis, Gardenia Ornata, and Gardenia Vulcanica. I loved this paper and the illustrations that came with it. And I loved the names of the rosal varietals, which I found as beautiful as the given names of my mom and her Rosal siblings: Virtudes Rosal, Bernabella Rosal, Paraluman Rosal, Sonia Rosal, Aurelita Rosal, Norma Rosal, Victoria Rosal, Teresita Rosal, Araceli Rosal, and last but not least, my tito, the youngest, Aurelio Rosal, Jr. 11

On the day of my appointment, I broke the news to Zee, my tattoo artist.12 She gracefully abandoned the rose part of her sketch and freehanded the gardenia on my arm. I had not gotten much sleep the night before. I slept through the entire session.

Peeling back the petals

You would think that this would put a nice big bow on the question of my middle name. Finally! Something concrete about who I am and where I come from that my middle name can actually speak to.

And yet, and yet… I still have a feeling that there are an infinite number of petals to peel before I’ll ever get to the... hm, what do you call what’s in the middle of the petals of a flower?13 The bud? Or is the bud what was there before the pedals bloomed? And should I have used the word “pluck” instead of “peel”? I don’t know. But I guess that’s my point.

For example, here’s a question. Why would Rosal, a Spanish word that means “rose garden” in Spanish, mean “gardenia” in Tagalog?14 I have theories, but only theories. Here is one. It’s based on the fact that roses grow well in warm climates, like in many parts of Europe, but they have difficulty growing in tropical environments, like in the Philippines. Gardenias, meanwhile, are native to the tropics, and certain varietals, like that Gardenia Jasminoides, produce flowers that look very similar to roses. What if Spanish colonists arriving in the Philippines back in the 16th and 17th centuries were eager to recreate the same rosals that they had back in Spain? What if they tried roses, but roses wouldn’t grow? So they used the local gardenias as a substitute, because they looked like white roses. It was easy just referring to their gardenia gardens using the same word they used to refer to their rose gardens, rosal. And so, in the Philippines, “rosal” came to mean gardenia, even though gardenias were not real rosals at all. One theory, at least.

Here is another question. Why in the Philippines is it traditional to give your child a middle name after the mother’s maiden name? I have a theory for this one too. Maybe it was a way of dealing with the hundreds of years of muddled ancestral history. An attempt to preserve as much lineage as possible. Even if for just one generation longer.

I even started having questions about me and my tattoo as I wrote this post. Like: why did I ask Zee to tattoo a Gardenia Vulcanica on my arm (one of the varietals in K.M. Wong’s paper), when this particular varietal looked nothing like the Gardenia Jasminoides that grew on my mom’s fence? Wasn’t the point to connect with her past?

I thought a lot about this one. Here goes. I remember liking the Gardenia Vulcanica because it is one of the varietals that are endemic to the Philippines. I suppose that I was not only interested in connecting with my mom’s Filipino roots. I was also interested in connecting with her indigenous roots. That was the desire, at least.

I also liked the fact that Gardenia Vulcanica grows on the volcanic soil of Luzon island. At the time (and still), I was living on the volcanic soil of Oahu, Hawai’i. I suppose choosing this varietal was, in a way, a sort of celebration of my current life in Hawai’i. I was interested in representing not only where my family came from in the past, but where I find myself now. It is the two put together that shapes me. And will continue to.

Finally, I liked that “vulcanica” kind of sounds like Vulcan, one of the alien races in the show Star Trek. First Officer Spock is half-Vulcan, half-human. He is mixed-race. Like me. So I liked that. Also, Vulcans are logical thinkers. As much as Spock tries to assert Vulcan-like control over himself and his circumstances, his real and messy emotions, i.e. what makes him human, has a way of coming out. Here’s the thing about that. We the audience do not fault Spock for this. We love him for it.

Parties

The Rosal clan abandoned the physical fences of their Quezon City home in the early 70s, around when President Ferdinand Marcos announced on television that he had placed the entire country under martial law. It wasn’t a safe place to live. The entire family moved to America. All except for my mom and her younger sister, Araceli. The two stayed behind to look after the house. There were mornings on my mom’s walk to the hospital (she was a nurse) when she stepped by corpses of people who were shot dead for staying out past curfew. The two held out for a couple of years until finally, when my mom was 23, they came to New York.

The sisters started families of their own in the New York City area. Growing up, we had massive family parties at my Tita Vir’s home in Rockland County. I remember we would just refer to her house as “Rockland.” We’re going to Rockland this weekend, mom would say. For a long time, I didn’t know that Rockland was the name of the entire county. I just thought it was the name of the house.

Those parties were a blast. There would be my titas (aunts) and my uncles and my thirty-or-so cousins. We ran around, we played volleyball in the front yard. We swam in the pool out back. We ate Filipino pork BBQ. We played Nintendo. We had massive sleepovers. Imagine dozens of snoring bodies strewn about the floor. Going to the bathroom in the middle of the night was like walking through a minefield.

I can tell you that my titas were the heart of these parties. They laughed and gossiped, they shrieked about God knows what, they scolded me and the cousins, they kissed and adored me and the cousins. My uncles were happy to be on the sidelines. They cracked jokes, they drank beer, they passed out on couches. My dad, the Jew from New Jersey, found a way of mixing in with them.

Today, many of my cousins are married with kids of their own. The “Rosal clan” is even more colorful. I think of this medley of people, joined together from different corners of the world, and I think maybe our middle names are not meant to complete us. Nor are they meant to be an impenetrable garden fence. Maybe our middle names are here to remind us of the many things that make us incomplete. Not to patch that fence up. But to wear our gardens on it. To accompany it. And to celebrate it. So that in our incompleteness, we can be together. So that with it, we can party.

◆

Footnotes

Jacob’s middle name is Andrew.

Jesse’s middle name is Lennon. Only recently did Arel inform Jesse that when I was a child, I wanted “Jesse” as my middle name after him. It delighted him. He will remind me of it now and then.

Or probably to keep the church off the family’s back for not making the child’s first name a Saint name.

I didn’t know it was standard Filipino practice until I did a little research on it for this here post. But it says it right there in Wikipedia.

My mom Victoria’s middle names are Lourdes and Ferrer. My dad Richard’s middle name is Hanan.

Spit-roasted pig slowly rotisseried over open coals.

Basketball became prevalent in the Philippines after America acquired the islands from the Spanish in 1898. Today, it is the most popular sport in the country. Once, my cousin and I played a pickup game with two local kids on a remote island in Palawan, and they destroyed us.

My mom did medical school in the Philippines for one year, but she didn’t like it.

There were three women of 20. But the teachers only called on men. They weren’t paying attention to the women. I couldn’t deal with studying with men who thought they were gods. I wasn’t really sure I wanted to be a doctor anyway. I liked being a nurse, I liked talking to patients. The doctors never talked to patients anyway. They would just give the diagnosis and leave. Except for your dad, of course.

Shana’s middle name is Rosal.

Shana had the idea of doing a hamsah for her tattoo, a symbol across cultures known for warding off evil and inviting positivity. She would put the rose in the palm area of the symbol. I had the idea of doing a tortenheber, the german word for pie-server, with the shape of a rose in the handle. #dylanmakespie

They share the middle name Ferrer, which was their mother’s maiden name. My mom, like my brother, has two middle names. Now that her last name is Greif, her full name is: Victoria Lourdes Ferrer Rosal Greif. Lourdes is French, after the hospital she was born in, Our Lady of Lourdes, run by French nuns.

You can see Zee’s work on Instagram.

It’s a pistil!

The Spanish word for one single rose is rosa. The Tagalog word for one single rose is similar, rosas. But to say rose bush in Tagalog, my mom would use a sort of Tagalog-English mix: bush ng rosas. To say rose garden would be a Tagalog-Spanish mix: jardin ng rosas.